Barry Jean Ancelet & Sam Broussard

“Poetry in Motion — Cajun Stories Woven into Sound”

Quick Intro

Barry Jean Ancelet & Sam Broussard unite Ancelet’s stature as a folklorist, poet, and champion of Cajun culture (writing under the pseudonym Jean Arceneaux) with Broussard’s masterful multi-instrumental artistry and production savvy. Together, they’ve created daring, genre-defying work that melds Cajun tradition with art-rock, jazz, electronic textures, and poetic storytelling.

In-Depth Profile

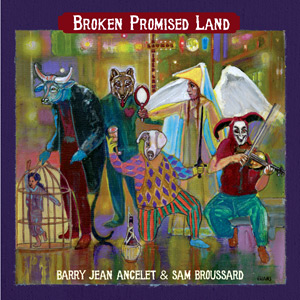

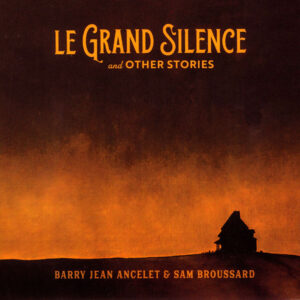

Their collaborative story began when Ancelet handed transformative minimalist lyrics to Broussard, sparking the influential track “Menteur,” later featured on Steve Riley’s Best Of collection. That partnership culminated in their 2016 release, Broken Promised Land, a Grammy-nominated album in the Regional Roots category produced and performed almost entirely by the duo. In 2024, they followed up with Le Grand Silence and Other Stories, a richly layered and instrumentally dense album featuring virtually all instrumentation by Broussard, inspired by the varied rhythms and textures of Ancelet’s lyrics. Broussard plays a staggering range—guitars, banjitar, African finger piano, piano with effects, fiddle, flute, and more—bringing their poetic visions to expansive musical life.

Signature Tracks

- “Menteur” — the track that launched their powerful collaborative voice

- “Conte de faits” — opener on Broken Promised Land that unfolds like a cinematic blues narrative

- “Le Grand Silence” — the haunting waltz centerpiece from their second album

Notable Accomplishments & Awards

- Broken Promised Land (2016) — Grammy nominated for Best Regional Roots Music Album

- Le Grand Silence and Other Stories (2024) — critically acclaimed follow-up with richly textured arrangements

- “Late in Life” (written by Ancelet and Wayne Toups) — CFMA Song of the Year

- Barry Jean Ancelet — named Living Legend by the Acadian Museum; honored by CFMA chapters

- Barry Jean Ancelet — chevalier in both the Ordre des Palmes Académiques and the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (France)

- Barry Jean Ancelet — 2024 Cajun Music Festival Honoree

Bonus Notes

- Lyrics and music balance French and English, enhancing accessibility across audiences

- Broussard’s instrumental palette includes guitars, banjitar, African finger piano, piano with accordion-like effects, fiddle, flute, harmonica, sax, and more

- Ancelet’s cultural contributions extend to founding Festivals Acadiens, directing the Center for Acadian and Creole Folklore, hosting “Rendez-Vous des Cajuns” on KRVS, and preserving media archives

Album Reviews

Broken Promised Land

OffBeat Magazine — Written by Dan Willging (September 2016)

“This set is a brilliant showcase of Ancelet’s thought-provoking poetry and Broussard’s genius arrangements.”

For decades now, retired ULL professor Barry Ancelet has written French language poems and lyrics under the pseudonym of Jean Arceneaux. A few have been recorded, such as “Late in Life,” the 1992 CFMA Song of the Year that was co-written with Wayne Toups. The roots of this collaboration began when Ancelet gave Mamou Playboys’ guitarist Broussard some minimalist lyrics that blossomed into the electrifying “Menteur” found on Steve Riley’s 2008 Best Of disc.

Interestingly, for being an account of Amédé Ardoin towards the end of his life, “Une Dernière Chanson” is a surprising steel guitar and fiddle–fueled country two-stepper. The despairing loneliness of “Appuyé Dessus la Barre” is folk-centric and haunting, yet replete with a beautiful, sunny solo.

As Ancelet’s poems vary in subject, Broussard counters with creative arrangements to suit whatever’s on hand, whether it’s a protest rocker (“Trop de Pas”), a wall-rattling bluesy howl (“Le Loup”), or a densely layered, poignant ballad (“Personne Pour Me Recevoir”). While Ancelet and Broussard alternate vocals and occasionally harmonize, Anna Laura Edmiston blows the doors off with her enchanting performance of “Coeur Cassé.”

To break up the vocal content, Broussard tosses in a quasi-orchestral instrumental—“Pour Qui?”—that’s simultaneously jazzy and cinematic. A rare recording that gets deeper with each and every listen.

Le Grand Silence and Other Stories

OffBeat Magazine

“The duo’s highly anticipated Le Grand Silence and Other Stories not only picks up where its predecessor left off, but skips a few chapters ahead.”

Sometime in the 1980s, then University of Louisiana Professor Barry Jean Ancelet began writing French-language poetry under the nom de plume of Jean Arceneaux. Some were ultimately reworked into song lyrics; others were initially written as lyrics. Ancelet reasoned that most Louisiana French literature was consumed as song lyrics. Over the decades, Steve Riley & the Mamou Playboys, Kevin Naquin, Richard LeBouef, and Jambalaya have recorded Ancelet’s lyrics. In 1991, Wayne Toups won the Cajun French Music Association Song of the Year with Ancelet’s “Late in Life.” In 2014, Ancelet’s lifelong friend, Sam Broussard, a singer/songwriter in Riley’s band, expressed interest in transforming his lyrics into musical compositions. Broussard likens his methodology to the Brazilian model of songwriting, where a composer pairs with the best lyricist possible, and for French lyrics, he estimates Ancelet is the best. Obviously, the symbiotic partnership works. Their first recording, Broken Promised Land, was Grammy-nominated in 2016.

Eight years later, the duo’s highly anticipated Le Grand Silence and Other Stories not only picks up where its predecessor left off, but skips a few chapters ahead. Compared to its predecessor, the arrangements are exponentially more complex and denser. Any instrument not played by one of the seven guests—mostly drummers and harmonica players (including Zachary Richard)—is played by Broussard under the humorous summarization of “Everything but …,” as noted in the detailed liner notes.

Broussard says his inspiration for the arrangements comes from the rhythms of Ancelet’s lyrics. The proceeding’s many themes led to Broussard’s weaving of varied and amazing textures. The haunting “Ouindégo” begins with Broussard’s hypnotic finger-picking pattern and soft, delicate vocal delivery on a tale about a mysterious children-munching swamp spirit whose invisible presence causes it to become windy. Orchestral parts float in, which also close the song with a surreal moment. “Grand Silence” is the only traditional Cajun track, a fiddle-driven waltz. It’s about finding solitude while paddling through the swamp and the tranquility and introspection it brings.

Broussard does intriguing things with his vocals and those of his participants. “Entre Deux” and “Feufollet” have shades of African American harmonies but may remind some of South Africa’s Ladysmith Black Mambazo. “J’ai Pas Fair Ça” breaks its intensity twice to shift into a melodic multi-part quasi-juré.

In the liner notes, Broussard lists himself as the light voice and Ancelet as the dark. Dark often fits Ancelet’s low register and the parts he sings, but it also is an apt description of his lyrics, such as “Ouindégo,” “J’ai Pas Fair Ça,” and “Pieds du Diable.” “Trop Jeune” describes an older man past his prime. Broussard’s rhythmic pattern on the piano’s low bass notes feels ominous, possibly that the end is near. Yet, nothing is more disturbing than the macabre “Conséquences,” a young girl is beaten senselessly to the point of madness and abandoned.

Besides Broussard singing lead on most songs and Ancelet on some, Anna Laura Edmiston is the only other lead vocalist. On tearful “Si Je T’aimais,” she is simply stunning in her admission of unrequited love. The arrangement’s pauses and swells augment the emotion portrayed.

Broken Promised Land

KnowLouisiana.org — Written by Ben Sandmel (Winter 2016)

“Despite Swallow Records’ extensive catalogue, it is unlikely that anything in its vast vaults bears much resemblance to ‘Broken Promised Land’—a brilliant, edgy, genre-defying album by Barry Jean Ancelet and Sam Broussard.””

Since 1958 the Ville Platte–based Swallow Records and its subsidiary labels have released a wealth of Cajun, zydeco, and swamp-pop classics. Despite this extensive catalogue it is unlikely that anything in Swallow’s vast vaults bears much resemblance to its newly released “Broken Promised Land”—a brilliant, edgy, genre-defying album by Barry Jean Ancelet and Sam Broussard. Ancelet has devoted his eminent career to the study and documentation of French Louisiana’s cultural, linguistic and folkloric traditions, and their connections with the rest of the French-speaking world. Accordingly it may seem like a radical departure for him to contribute all the lyrics, and four lead vocals, to this startling project produced by Broussard. “Broken Promised Land” encompasses art-rock, electronic music, and futuristic abstract soundscapes, as well as syncopation and poly-rhythms, passages of jazz and classical music, searing guitar solos, exquisitely subtle interludes, and the distinct influence of both The Beatles and The Band, alongside Cajun music, zydeco and country. In addition to this improbably rich mélange, some of the songs’ structures—the poignant “Appuyé dessus la barre,” for one—take fascinatingly circuitous paths before harmony and melody resolve at the end of each verse.

For a sense of how this freewheeling approach holds together, consider the album’s opening song, “Conte de faits.” It starts with bluesy guitar chords and stinging single-note licks played over ambient effects that suggest both howling winds and police sirens. These fade, but the guitar builds throughout the intro and continues after Broussard’s vocal comes in. His first verse is followed by a lengthy guitar solo with dramatically increasing intensity, underpinned by the introduction of a drumbeat with a metallic/industrial sound. Broussard plays the latter part of this solo over descending figures provided by a horn section that appears unexpectedly, contributes its part succinctly, and then vanishes. The second verse finds Broussard singing at full throttle, accompanied towards the end by back-up vocals with a gospel-music tinge—and then the song abruptly stops cold.

Broussard demonstrates national-level production skills by binding these disparate and wildly imaginative strands into a cohesive whole. The most dramatic examples are “Conte des faits,” “Trop de pas,” “Personne pour me recevoir,” and “Pour qui?” Other songs unfold in a more straightforward manner that reveals a core of Cajun music, zydeco, and country. The result is an ambitious yet fully realized project that is unique in the history of French Louisiana’s music. Appearing less than a year after the release of “I Wanna Sing Right: Rediscovering Lomax in the Evangeline Country” (see Sound Advice, Spring 2016)—which was also groundbreaking, in a different sense—“Broken Promised Land” underscores the impressive musical creativity that is absolutely surging today in southwest Louisiana.

Broussard, who currently plays guitar with the Cajun band Steve Riley and the Mamou Playboys, is a multi-instrumentalist, a bilingual singer and a songwriter with decades of professional experience in the United States, Europe and Africa. He has released two solo albums, “Veins” and the critically acclaimed “Geeks.” Broussard sings lead on six of the songs here, and his expressive voice can run the gamut from plaintive (“Personne pour me recevoir”) to urgent (“Conte des faits”). Ancelet can likewise range from wistful (“Appuyé dessus la barre”) to ominous (“Le loup”), as the moment demands. Anna Laura Edmiston contributes a gorgeous vocal on the pensive waltz“Coeur Cassé.” Broussard plays almost all of the instruments here, overdubbed, with David Greely and Gina Forsyth adding fiddle parts and Christine Balfa and Danny Devillier making rhythmic contributions on triangle and drums, respectively.

Since 1980 Ancelet has been writing widely published poetry in French, under the nom de plume Jean Arceneaux. “Broken Promised Land” consists entirely of Ancelet’s poems set to music. “Sam and I worked on this project for our own enjoyment, in his own studio,” Ancelet recalls, “so we had the luxury of unlimited time to experiment with ideas. I respect Sam deeply, we are life-long friends, and I learned so much about the craft of singing from him that I feel I owe him tuition. Sam came up with most of the tunes and basic arrangements, but we talked constantly about what to do with each song. . . . We were both interested in representing our varied backgrounds that include the blues, rock, country, Cajun, zydeco, jazz and pop . . . our ’60s roots.”

Broussard similarly cites ’60s music as influencing his production sensibilities: “What that era gave to me was a higher proportion of pop songs that had great lyrics and melodies, chord changes that were interesting just on their own, and brilliant instrumentation.” Broussard also “took two semesters of theory and composition a long time ago. Learning Bach four-part writing was life-changing. And,” he concludes,“I have to give a bow to our engineer, Tony Daigle” for his contributions to this technically complex project.

Ancelet’s lyrics (English translations of which appear in the liner notes) are at times disquieting, as on “Conte de fait”:

“All the children escaped

When the devil left open

The door of the cage that he had made

To capture and tame them long ago

“The devil chases them

And finds them all, except for the tricky one

Who had hidden in the cage.

To avoid the rage, the rage of the devil,

The devil fooled.”

“I sometimes focus on dark themes,” Ancelet says. “I push myself into an improvised nightmare and then write out of that. But there are other issues on this album, including a condemnation of the manipulated violence in the world, a questioning of the trappings of organized religion, and an exploration of the tension between French-based and English-based identities, tradition-based and modern-based identities.” He also points to other influences that shape the album: “There’s a song written in the voice of Amédé Ardoin, and a celebration of the Creole storyteller Ben Guiné, from Promised Land, a rural area on Bayou Teche near Parks in St. Martin Parish.” These themes are additionally reflected in the surreal cover art by the gifted Lafayette painter Olin “Leroy” Evans.

LCV readers who do not speak French will nonetheless find considerable substance on this remarkable album. The emotions conveyed transcend language. And the instrumental settings offer new sonic revelations with each successive listening.